Graham Reynolds composes and conceives of music as a man of his time. Perhaps that's more true of some than others, but Maestro Reynolds most definitely fits with his time, in whatever ways that can be. Our century is no doubt too new to understand where we are and are going, what we are becoming, what future generations will think and say about us. That's inevitable. One can never be sure what the final judgement (never will happen) would be on our times in the murky nethers of hundreds of years in the future. So we press on, mindful that we act in the company of future generations (they as spectators), but unable to speak with them directly. Such is as it has always been.

One thing does seem clear, to me at least. That is, that the neatly divided musical genres that seemed so sacrosanct in, say, 1950, have become fluid and subject to flux. Perhaps they are undergoing transformation into sets of something other, like caterpillars into butterflies.

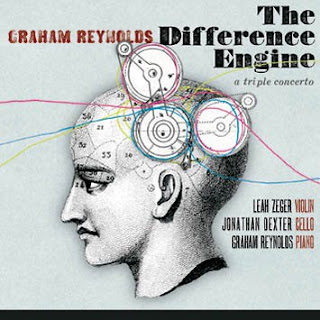

So we have Graham Reynolds' new work, The Difference Engine (Innova 790), a triple concerto for violin, cello, piano, and chamber string orchestra. Triple concertos are something that the Baroque through Romantic Ages seemed to favor, more so than today at any rate. The form obviously has life left in it. After all, it's a way to have maximal solo color to contrast with the larger orchestral texture.

Graham Reynolds has constructed a work that puts me in mind of the delicate whimsy of remembrance and a sense of the shifting sands of life at times; other times there is a certain motor insistency that you could say comes out of rock and/or hip hop, but not in any obvious way. It is a very attractive, inventive work. The soloists Leah Zeger, violin, Jonathan Dexter, cello, and Mr. Reynolds himself at the piano combine virtuostic dash with a interpretive stance that is emotionally redolent without being mawkish. There is a shade of neo-classical restraint that appeals, to me anyway.

So if Reynolds stopped there, one would be satisfied that a contemporary work of breadth, charm, and eventful content had been well performed, and that would be that. He does not. The second half of the disk is a series of remixes of all five movements, each one taken by a different artist. (By "remix" it is not a matter of shifting a balance of tones here and there, but rather a reworking of the musical material in the studio, adding instruments, adding musical motifs, resituating motifs in new contexts, etc.). Octopus Project takes a movment, as does Reynolds himself. So does Adrain Quesada, Peter Stopschinski, and the redoubtable DJ Spooky.

The result is sometimes a beats version of a movement, sometimes a minimalist-rock recasting, sometimes a creative chopping, sometimes a kind of electronica-meets-organica situation. The second half brings the so-called "ivory tower" neo-classicism with its particular integrity out onto the street, where it learns to chill and act in new ways according to the dictates of its new world.

Now this would be a rather moot situation if the remixes didn't work--if either the original music itself or the re-treatment of it (or both) failed to connect. That is certainly not the case here. The conventional piece and the remixed movements illuminate one another, put phrases in new contexts and resituate what once was on sacred ground onto another spatial configuration altogether.

I don't want to sound anything more than historically illuminative when I add that this sort of thing has been happening on the rock turf since the later '60s (for better or worse) with the Moody Blues, King Crimson, Zappa and many groups that followed in the prog rock realm, as well as various experiments in fusion and third stream jazz, and some of the orchestral-jazz hybrids put together by artists associated with the ECM label. That is only to say that this music has precedent. And I leave out similar endeavors that have taken place on the solidly classical side (Bernstein and a fairly long list).

The point though is that Graham Reynolds injects life into his music by subjecting it to the second, remix process. The remixes succeed because the music lends itself to reconfiguration and the remixers have applied their alterations with a genuine affection and respect for the original score.

This is a fascinating, exhilarating, and probably, an indispensable disk for those who have an open mind. And it's beautiful music.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment